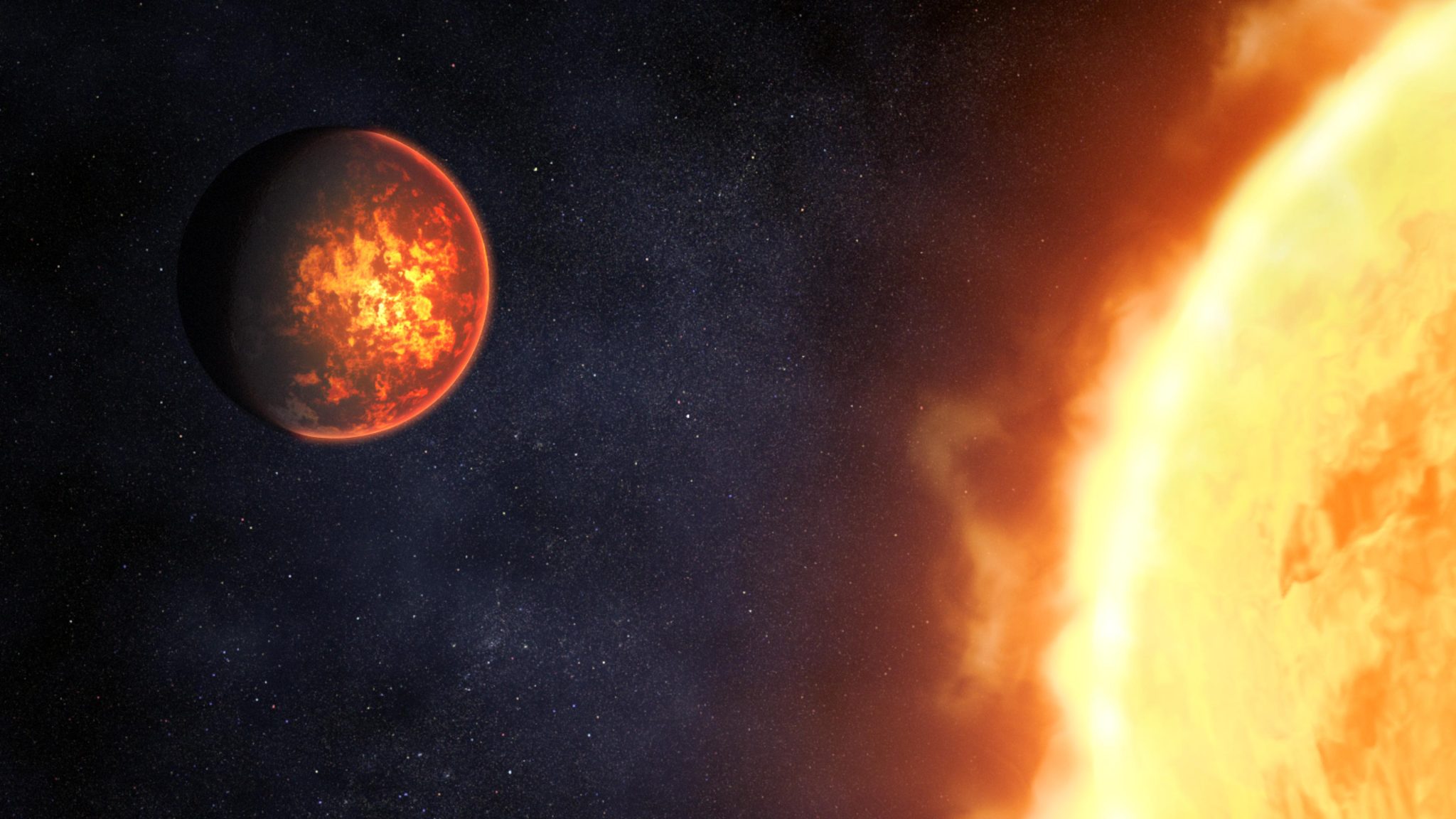

Illustrasjon som viser hvordan eksoplanet 55 Cancri e kan se ut, basert på nåværende forståelse av planeten. 55 Cancri e er en steinete planet med en diameter som er nesten dobbelt så stor som Jorden og kretser bare 0,015 astronomiske enheter fra sin sollignende stjerne. På grunn av sin tette bane er planeten ekstremt varm, med dagtemperaturer som når 4400 grader Fahrenheit (omtrent 2400 grader Celsius). Spektroskopiske observasjoner ved hjelp av Webbs nær-infrarøde kamera (NIRCam) og Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) vil bidra til å avgjøre om planeten har en atmosfære eller ikke, og i så fall hva atmosfæren er laget av. Observasjonene vil også bidra til å avgjøre om planeten er tidevannslåst eller ikke. Kreditt: NASA, ESA, CSA, Dani Player (STScI)

Astronomer vil trene Webbs høypresisjonsspektrografer på to spennende steinete eksoplaneter.

Tenk om jorden var mye, mye nærmere solen. Så nærme at et helt år bare ville vart noen få timer. Så nærme at tyngdekraften har låst den ene halvkulen i permanent brennende dagslys og den andre i evig mørke. Så nærme at havene koker bort, steiner begynner å smelte, og skyene regner lava.

Selv om ingenting slikt eksisterer i vårt eget solsystem, er planeter som dette – steinete, omtrent på størrelse med jorden, ekstremt varme og nær stjernene deres – ikke uvanlig i[{” attribute=””>Milky Way galaxy.

What are the surfaces and atmospheres of these planets really like?

Illustration showing what exoplanet LHS 3844 b could look like, based on current understanding of the planet.

LHS 3844 b is a rocky planet with a diameter 1.3 times that of Earth orbiting 0.006 astronomical units from its cool red dwarf star. The planet is hot, with dayside temperatures calculated to be greater than 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (greater than about 525 degrees Celsius). Observations of the planet’s thermal emission spectrum using Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) will provide more evidence to help determine what the surface is made of. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Dani Player (STScI)

Geology from 50 Light-Years: Webb Gets Ready to Study Rocky Worlds

With its mirror segments beautifully aligned and its scientific instruments undergoing calibration, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (Webb) is just weeks away from full operation. Soon after the first observations are revealed this summer, Webb’s in-depth science will begin.

Included in the investigations planned for the first year are studies of two hot exoplanets classified as “super-Earths” for their size and rocky composition: the lava-covered 55 Cancri e and the airless LHS 3844 b. Scientists will train Webb’s high-precision spectrographs on these planets with a view to understanding the geologic diversity of planets across the galaxy, as well as the evolution of rocky planets like Earth.

Super-Hot Super-Earth 55 Cancri e

55 Cancri e orbits less than 1.5 million miles from its Sun-like star (one twenty-fifth of the distance between Mercury and the Sun), completing one circuit in less than 18 hours. With surface temperatures far above the melting point of typical rock-forming minerals, the day side of the planet is thought to be covered in oceans of lava.

Illustration comparing rocky exoplanets LHS 3844 b and 55 Cancri e to Earth and Neptune. Both 55 Cancri e and LHS 3844 b are between Earth and Neptune in terms of size and mass, but they are more similar to Earth in terms of composition.

The planets are arranged from left to right in order of increasing radius.

Image of Earth from the Deep Space Climate Observatory: Earth is a warm, rocky planet with a solid surface, water oceans, and a dynamic atmosphere.

Illustration of LHS 3844 b: LHS 3844 b is a hot, rocky exoplanet with a solid, rocky surface. The planet is too hot for oceans to exist and does not appear to have any significant atmosphere.

Illustration of 55 Cancri e: 55 Cancri e is a rocky exoplanet whose dayside temperature is high enough for the surface to be molten. The planet may or may not have an atmosphere.

Image of Neptune from Voyager 2: Neptune is a cold ice giant with a thick, dense atmosphere.

The illustration shows the planets to scale in terms of radius, but not location in space or distance from their stars. While Earth and Neptune orbit the Sun, LHS 3844 b orbits a small, cool red dwarf star about 49 light-years from Earth, and 55 Cancri e orbits a Sun-like star roughly 41 light-years away. Both are extremely close to their stars, completing one orbit in less than a single Earth day.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Dani Player (STScI)

Planets that orbit this close to their star are assumed to be tidally locked, with one side facing the star at all times. As a result, the hottest spot on the planet should be the one that faces the star most directly, and the amount of heat coming from the day side should not change much over time.

But this doesn’t seem to be the case. Observations of 55 Cancri e from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope suggest that the hottest region is offset from the part that faces the star most directly, while the total amount of heat detected from the day side does vary.

Does 55 Cancri e Have a Thick Atmosphere?

One explanation for these observations is that the planet has a dynamic atmosphere that moves heat around. “55 Cancri e could have a thick atmosphere dominated by oxygen or nitrogen,” explained Renyu Hu of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, who leads a team that will use Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) to capture the thermal emission spectrum of the day side of the planet. “If it has an atmosphere, [Webb] har følsomheten og bølgelengdeområdet for å oppdage det og bestemme hva det er laget av,» la Hu til.

Eller regner det lava om kvelden på 55 Cancri e?

En annen spennende mulighet er imidlertid at 55 Cancri e ikke er tidevannslåst. I stedet kan det være som Merkur, som roterer tre ganger for hver to omløp (det som er kjent som en 3:2-resonans). Som et resultat ville planeten ha en dag-natt-syklus.

“Det kan forklare hvorfor den varmeste delen av planeten er forskjøvet,” forklarte Alexis Brandeker, en forsker fra Stockholms universitet som leder et annet team som studerer planeten. “Akkurat som på jorden, ville det ta tid før overflaten varmes opp. Den varmeste tiden på dagen vil være på ettermiddagen, ikke rett ved middagstid.»

Mulig termisk emisjonsspekter for den varme superjordeksoplaneten LHS 3844 b, målt med Webbs Mid-Infrared Instrument. Et termisk emisjonsspekter viser mengden lys av forskjellige infrarøde bølgelengder (farger) som sendes ut av planeten. Forskere bruker datamodeller for å forutsi hvordan en planets termiske utslippsspekter vil se ut under forutsetning av visse forhold, for eksempel om det er en atmosfære eller ikke og hva overflaten til planeten er laget av.

Denne spesielle simuleringen antar at LHS 3844 b ikke har noen atmosfære og dagsiden er dekket av den mørke vulkanske bergarten basalt. (Basalt er den vanligste vulkanske bergarten i vårt solsystem, og utgjør vulkanske øyer som Hawaii og det meste av jordens havbunn, samt store deler av overflatene til Månen og Mars.)

Til sammenligning representerer den grå linjen et modellspekter av basaltisk bergart basert på laboratoriemålinger. Den rosa linjen er spekteret av granitt, den vanligste magmatiske bergarten som finnes på jordens kontinenter. De to bergartene har svært forskjellige spektre fordi de er laget av forskjellige mineraler, som absorberer og sender ut forskjellige mengder forskjellige bølgelengder med lys.

Etter at Webb har observert planeten, vil forskerne sammenligne det faktiske spekteret med modellspektre for ulike bergarter som disse for å finne ut hva overflaten til planeten er laget av.

Kreditt: NASA, ESA, CSA, Dani Player (STScI), Laura Kreidberg (MPI-A), Renyu Hu (NASA-JPL)

Brandekers team planlegger å teste denne hypotesen ved å bruke NIRCam for å måle varmen som sendes ut fra den opplyste siden av 55 Cancri e under fire forskjellige baner. Hvis planeten har en 3:2 resonans, vil de observere hver halvkule to ganger og skal kunne oppdage enhver forskjell mellom halvkulene.

I dette scenariet ville overflaten varmes opp, smelte og til og med fordampe i løpet av dagen, og danne en veldig tynn atmosfære som Webb kunne oppdage. Om kvelden ville dampen avkjøles og kondensere for å danne dråper av lava som ville regne tilbake til overflaten, og bli fast igjen når natten faller på.

Noe kjøligere Super-Earth LHS 3844 b

Mens 55 Cancri e vil gi innsikt i den eksotiske geologien til en verden dekket av lava, LHS 3844 b gir en unik mulighet til å analysere det faste fjellet på en[{” attribute=””>exoplanet surface.

Like 55 Cancri e, LHS 3844 b orbits extremely close to its star, completing one revolution in 11 hours. However, because its star is relatively small and cool, the planet is not hot enough for the surface to be molten. Additionally, Spitzer observations indicate that the planet is very unlikely to have a substantial atmosphere.

What Is the Surface of LHS 3844 b Made of?

While we won’t be able to image the surface of LHS 3844 b directly with Webb, the lack of an obscuring atmosphere makes it possible to study the surface with spectroscopy.

“It turns out that different types of rock have different spectra,” explained Laura Kreidberg at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy. “You can see with your eyes that granite is lighter in color than basalt. There are similar differences in the infrared light that rocks give off.”

Kreidberg’s team will use MIRI to capture the thermal emission spectrum of the day side of LHS 3844 b, and then compare it to spectra of known rocks, like basalt and granite, to determine its composition. If the planet is volcanically active, the spectrum could also reveal the presence of trace amounts of volcanic gases.

The importance of these observations goes far beyond just two of the more than 5,000 confirmed exoplanets in the galaxy. “They will give us fantastic new perspectives on Earth-like planets in general, helping us learn what the early Earth might have been like when it was hot like these planets are today,” said Kreidberg.

These observations of 55 Cancri e and LHS 3844 b will be conducted as part of Webb’s Cycle 1 General Observers program. General Observers programs were competitively selected using a dual-anonymous review system, the same system used to allocate time on Hubble.

The James Webb Space Telescope is the world’s premier space science observatory. Webb will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.